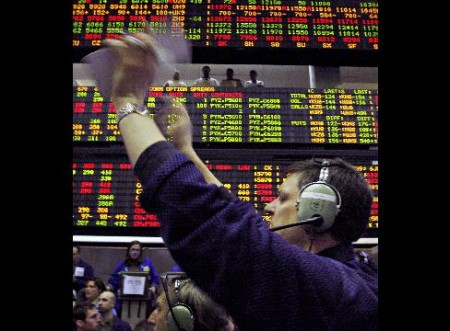

CHICAGO (Reuters) – U.S. corn futures soared more than 4 percent to a fresh record high for the fifth consecutive trading session on Wednesday as flooding expanded in the U.S. Midwest, harming the 2008 corn crop.

“There’s still no indication that we’re getting ready to change this pattern. Concerns continue from planting issues to emergence to crop development,” Mike Palmerino, forecaster for DTN Meteorlogix, said.

Corn prices on the Chicago Board of Trade have surged 80 percent over the past year, with nearly 17 percent of that tacked on just this month.

Soybeans surged 3 percent and wheat leaped nearly 5 percent as those markets followed corn, but the historic rainfall and flooding in the United States also were beginning to hurt soy and wheat crop prospects.

“There is definitely concern. There is way too much water and, even if it is drier next week, it won’t matter now. It’s too late to plant corn and even bean yields are being affected,” Vic Lespinasse, an analyst for GrainAnalyst.com, said.

Corn prices rallied the daily trading limit of 30 cents per bushel early in the session and the new-crop July 2009 contract soared to a record $7.56-1/4, surpassing the record of $7.35 set in during Asian trading hours.

By midday, U.S. corn for July 2008 delivery was locked up the 30-cent limit at $7.03-1/4 per bushel.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture this week slashed 5 bushels per acre from its estimate for U.S. corn yields because of excessive rainfall and flooding in key corn states, including top producers Illinois and Iowa.

Now there are ideas that yields and corn acreage will fall further because it keeps raining. This season has come the closest to the historic flood in summer 1993.

“That’s the year everyone is looking at as a comparison,” Palmerino said.

That summer the U.S. Midwest suffered from heavy flooding after weeks of rain that eventually caused the Mississippi River, a major North American river and grain shipping artery, to flood, washing out surrounding corn and soybean fields.

“The size of the corn crop is coming down, and maybe the wheat crop too,” said Chicago cash merchant Glenn Hollander of Hollander-Feuerhaken.

U.S. wheat markets leaped to keep up with corn and now the maturing winter wheat crop is being threatened by the rains.

Wheat for July delivery was up 58 cents per bushel at $8.67 per bushel at midday, nearing its 60-cent trading limit.

European grain markets followed the trends at the CBOT, extending their early rally. In Paris, the benchmark November wheat contract settled up 12.75 euros, or 6.6 percent, at 205 euros a tonne, after hitting 205.25 euros, its highest level since April 17.

“If you look at corn prices, wheat can only rise. We can’t have wheat cheaper than corn,” a European trader said.

U.S. traders said the excessive wet weather in the U.S. crop region was the main driver of the markets, but they also tied some of the gains to a strong rebound in crude oil and gold as the dollar fell.

“More rain is exactly what we don’t need, and today we have the added support from crude oil being up,” Lespinasse said.

U.S. soyoil, a key resource for the biodiesel industry, soared following crude oil, and soybean futures held to their own limit gains.

U.S. soy for July delivery was up its limit of 70 cents at $15.16-1/2 per bushel.

(Additional reporting by Christine Stebbins in Chicago and Sybille de La Hamaide in Paris; Editing by Walter Bagley)

By Sam Nelson

Wed Jun 11, 1:20 PM ET

Source: Reuters