Iran needs the price of oil to stay above $70 per barrel or it will go bust in 2009.

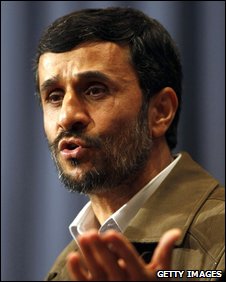

Presidential powers in Iran are often circumscribed by the clerics Presidential powers in Iran are often circumscribed by the clerics |

The sharp downward spiral of oil prices has prompted economists to predict that Tehran is facing severe financial hardship within the space of a few months.

Iran’s presidential contenders have to address the budget deficit brought about by the plummeting oil prices and the world banking crisis.

The country’s economy is almost totally dependent on oil, which accounts for 80% of the country’s foreign exchange receipts, while oil and gas make up 70% of government revenue.

Cash rolled in when the price of oil was above $140 a barrel and the country amassed huge foreign currency reserves, but with the price falling to around $40, that revenue has dried up accordingly.

For the first time since the Islamic revolution in 1979, Iranians will turn away from geopolitics and focus instead on the state of their economy when they go to the polls in June.

Impact of sanctions

On top of the recession and falling oil prices, Iran also has to grapple with sanctions imposed by the United States and the United Nations.

The US sanctions imposed in 1980, after the hostage-taking by students in Tehran, prohibit American citizens from having dealings with Iran.

They also make it difficult for other oil and gas companies to invest in Iran and then get US business.

The UN sanctions were imposed because of Iran’s alleged attempts to develop nuclear weapons by enriching uranium, something it denies.

Under those sanctions, the foreign assets of 13 Iranian companies are frozen, some officials are banned from travelling abroad and the sale of products with a possible military use is forbidden.

An advisor to the European Union, Dr Mehrdad Emadi-Moghadam from Staffordshire University in England, says the UN sanctions are more effective because they include regions and countries which were not co-operating with the US sanctions.

“Iran cannot enter into American or EU trade agreements, so it has been forced to acquire its goods though second parties,” he says.

“When it needs technology or commodities, Iran has to pay between 12 and 20% more than it would otherwise have cost them.”

Lagging behind

Being unable to update its technology has resulted in Iran having an antiquated manufacturing base.

In a country where the government is the biggest employer and the biggest contractor, companies are suffering from the harsh economic downturn.

“A number of our projects, mostly from ministries which have ordered them, have been halted because of a lack of funds,” says Ali Pahlavan, who works in an engineering company in Tehran.

“We are a one-product economy to some extent – diversification and modernisation has not taken place to the extent it should have,” he concedes.

He admits that many of the country’s problems are due to the sanctions, but says the government is also at fault.

“The revolutionary government pursues mostly ideological and political goals,” he says, “The economy has taken a back seat and is not the number one priority.”

Despite having a heavily state-controlled economy, there is a private sector operating in Iran.

“Iranians have always been innovative, but the private manufacture and construction sectors do not receive the kind of government support or regulation to help support exports,” Dr Mehrdad Emadi-Moghadam says.

Social expectations

The social problems of chronic and growing unemployment are also a cause for concern.

Despite its considerable oil wealth, the country still has 26% inflation and a high level of unemployment.

More than 35% of the population aged under 30 are experiencing long-term unemployment.

Dr Emadi-Moghadam sees a dichotomy, whereby one part of the population is very familiar with the latest Western innovations, while the other side is prevented from having access to ideas freely and connecting to the world economy through commercialising their ideas and activities.

As Iran commemorates its 30th anniversary of the revolution, he does not believe that it has achieved its stated objectives.

“When you take the overall view, Iran has actually regressed and is now in the bottom third of countries which receive foreign investment or perform well in international trade,” he says.

The country also performs badly in almost every internationally-recognised index of bribery and corruption.

Iran is one of the wealthiest nations as far as natural resources is concerned and its citizens expect the government to provide things such as cheap fuel.

Thirty years after the revolution, fuel is still heavily subsidised.

“The revolution was partly due to economics. Shah Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi couldn’t provide what the people wanted when the oil price dropped,” Dr Mehrdad Emadi-Moghadam says.

Clerical veto

By any orthodox standard, Iran’s economy is run in a bizarre fashion.

With its currency pegged to the US dollar, the regime’s petrodollars are worth less and less every year and the government is unable to put up taxes, because such a move would be too unpopular.

The president has been attempting to resolve some of the difficult economic decisions the government has to make.

He recently introduced an Economic Reform Plan, with the aim of enabling the government to reduce dependence on oil revenues and tackling the country’s economic problems, including rising inflation.

The plan would cut costly energy subsidies and redistribute a larger portion of the sum among citizens.

Twelve million of Iran’s population of 69 million live in the capital. Twelve million of Iran’s population of 69 million live in the capital. |

The president says only his original proposal could achieve the objectives his government seeks in maintaining the economy, but it has not been approved by lawmakers.

The government had asked for $35bn to implement the plan, but parliament only approved $8.5bn.

Although Iran is a democracy, the clerics have veto powers over any legislation.

When Mahmoud Ahmadinejad campaigned for his present position, he fought on a platform of fighting corruption and achieving fairness in distribution of revenue.

Dr Mehrdad Emadi-Moghadam says the president has failed on all accounts in the last four years and his achievements, or lack of them, will play a key role in the forthcoming elections.

Page last updated at 00:04 GMT, Friday, 27 February 2009

By James Melik

Business reporter, BBC World Service

Source: BBC NEWS