At least 29 states plus the District of Columbia, including several of the nation’s largest states, faced an estimated $48 billion in combined shortfalls in their budgets for fiscal year 2009 (which began July 1, 2008 in most states.) At least three other states expect budget problems in fiscal year 2010.

In general, states closed these budget gaps through some combination of spending cuts, use of reserves or revenue increases when they adopted a fiscal year 2009 budget. At this point in the year, most states have already adopted those budgets; only two states – California and Michigan – continue to deliberate.[1] In order to present a complete picture of the impact of the current economic downturn on state finances, we report both the gaps that have been closed and those that will be closed in the future.

The bursting of the housing bubble has reduced state sales tax revenue collections from sales of furniture, appliances, construction materials, and the like. Weakening consumption of other products has also cut into sales tax revenues. Property tax revenues have also been affected, and local governments will be looking to states to help address the squeeze on local and education budgets. And if the employment situation continues to deteriorate, income tax revenues will weaken and there will be further downward pressure on sales tax revenues as consumers become reluctant or unable to spend.

The vast majority of states cannot run a deficit or borrow to cover their operating expenditures. As a result, states have three primary actions they can take during a fiscal crisis: they can draw down available reserves, they can cut expenditures, or they can raise taxes. States already have begun drawing down reserves; the remaining reserves are not sufficient to allow states to weather a significant downturn or recession. The other alternatives – spending cuts and tax increases – can further slow a state’s economy during a downturn and contribute to the further slowing of the national economy, as well.

|

TABLE 1: |

||

|

Amount |

Percent of FY2008 General Fund |

|

| Alabama |

$784 million |

9.2% |

| Arizona |

$1.9 billion |

17.8% |

| Arkansas |

$107 million |

2.5% |

| California1 2 |

$22.2 billion |

21.3% |

| Connecticut |

$150 million |

0.9% |

| Delaware |

$217 million |

6.4% |

| District of Columbia |

$96 million |

1.5% |

| Florida |

$3.4 billion |

11.0% |

| Georgia |

$245 million |

1.2% |

| Illinois |

$1.8 billion |

6.6% |

| Iowa |

$350 million |

6.0% |

| Kentucky |

$266 million |

2.9% |

| Maine |

$124 million |

4.0% |

| Maryland |

$808 million |

5.5% |

| Massachusetts |

$1.2 billion |

4.2% |

| Michigan1 |

$472 million |

4.9% |

| Minnesota |

$935 million |

5.5% |

| Mississippi |

$90 million |

1.8% |

| Nevada |

$898 million |

13.5% |

| New Hampshire |

$200 million |

6.4% |

| New Jersey |

$2.5 – $3.5 billion |

7.6 – 10.6% |

| New York |

$4.9 billion |

9.1% |

| Ohio |

$733 million – $1.3 billion |

2.7 – 4.7% |

| Oklahoma |

$114 million |

1.6% |

| Rhode Island |

$430 million |

12.6% |

| South Carolina |

$250 million |

3.7% |

| Tennessee |

$468 million – $585 million |

4.2 – 5.2% |

| Vermont |

$59 million |

5.1% |

| Virginia |

$1.2 billion |

6.9% |

| Wisconsin |

$652 million |

4.8% |

| TOTAL |

$47.6 – $49.2 billion |

9.3 – 9.7% |

| 1These states have not yet adopted budgets for FY2009.2In a special session earlier this year, California adopted measures to close $7.0 billion of this shortfall. A gap of $15.2 billion remains to be closed. Assumes that FY08 gap would have carried over to FY09. | ||

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities currently is monitoring state fiscal reports and is in touch with state officials and/or relevant state nonprofit organizations in the 50 states and DC. The fiscal situation appears to be as follows.

- Over half of the states have faced problems with their FY2009 budgets.

- The 29 states in which revenues were expected to fall short of the amount needed to support current services in fiscal year 2009 are Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, and Wisconsin. In addition, the District of Columbia closed a shortfall in fiscal year 2009. The budget gaps totaled $47.6 to $49.2 billion, averaging 9.3 percent to 9.7 percent of these states’ general fund budgets. (See Table 1.) California – the nation’s largest state – faced the largest budget gap. The shortfalls that states other than California faced averaged 6.2 percent to 6.7 percent of these states’ general fund budgets.

- Analysts in three other states – Missouri, Texas, and Washington – are projecting budget gaps a little further down the road, in FY2010 and beyond. [2]

This brings the total number of states identified as facing budget gaps to 32 – close to two-thirds of all states. Most states have addressed the FY2009 budget gaps identified here. However, new budget gaps in these and other states are likely to develop as state revenue forecasts are updated during the year.

There are a number of reasons why some states have not been affected by the economic downturn. Some mineral-rich states – such as New Mexico, Alaska, and Montana – are seeing revenue growth as a result of high oil prices. Other states’ economies have so far been less affected by the national economic problems. This does not mean, however, that local governments in those states will escape fiscal stress. Some states with mineral revenues or with industries less affected by the national downturn have been affected by the housing bubble and could face widespread local government deficits.

In states facing budget gaps, the consequences could be severe – for residents as well as the economy. Unlike the federal government, states cannot run deficits when the economy turns down; they must cut expenditures, raise taxes, or draw down reserve funds to balance their budgets.

As a new fiscal year begins in most states, budget difficulties are leading some 21 states to reduce services to their residents, including some of their most vulnerable families and individuals.

Examples of enacted and proposed cuts to state services include[3]:

- Public health programs: At least 13 states have implemented or are considering cuts that will affect low-income children’s or families’ eligibility for health insurance or reduce their access to health care services. For example, Rhode Island has eliminated health coverage for 1,000 low-income parents, and New Jersey has cut funds for charity care in hospitals. California’s governor has proposed requiring many low-income families to pay more for their children’s health care.

- Programs for the elderly and disabled: At least seven states are cutting medical, rehabilitative, home care, or other services needed by low-income people who are elderly or have disabilities, or significantly increasing the cost of these services. For example, Florida has frozen reimbursements to nursing homes and relaxed staffing standards and Rhode Island is requiring low-income elderly people to pay more for adult daycare.

- K-12 education: At least 11 states are cutting or proposing to cut K-12 and early education; several of them are also reducing access to child care and early education. For example: Florida cut school aid by an estimated $130 per pupil, Nevada eliminated funds for gifted and talented programs, and Rhode Island is eliminating early education funding for 550 children. California is also proposing substantial K-12 cuts.

- Colleges and universities: At least 16 states have implemented or proposed cuts to public colleges and universities. For example, Alabama, Kentucky, and Virginia have all cut university budgets and/or community-college funding, resulting in tuition increases of 5 percent to 14 percent.

- State workforce: At least 15 states have proposed or implemented reductions to their state workforce. Workforce reductions often result in reduced access to services residents need. They also add to states’ woes by contracting the state economy. New Jersey is reducing its workforce by 2,000 employees through early retirement, lay-offs and attrition, leading an independent monitor to express concern about the impact on abused or neglected children losing experienced caseworkers; in Kentucky, the public defender will eliminate 10 percent of positions and decline certain types of cases; hiring freezes have been instituted in Arizona, California,Connecticut, Delaware, Minnesota, New Hampshire and Virginia.

If revenue declines persist as expected in many states, additional budget cuts are likely. The experience of the last recession is instructive as to what kinds of actions states may take as is likely. Between 2002 and 2004 states reduced services significantly. For example, in the last recession, some 34 states cut eligibility for public health programs, causing well over 1 million people to lose health coverage, and at least 23 states cut eligibility for child care subsidies or otherwise limited access to child care. In addition, 34 states cut real per-pupil aid to school districts for K-12 education between 2002 and 2004, resulting in higher fees for textbooks and courses, shorter school days, fewer personnel, and reduced transportation.

Expenditure cuts and tax increases are problematic policies during an economic downturn because they reduce overall demand and can make the downturn deeper. When states cut spending, they lay off employees, cancel contracts with vendors, eliminate or lower payments to businesses and nonprofit organizations that provide direct services, and cut benefit payments to individuals. In all of these circumstances, the companies and organizations that would have received government payments have less money to spend on salaries and supplies, and individuals who would have received salaries or benefits have less money for consumption. This directly removes demand from the economy. Tax increases also remove demand from the economy by reducing the amount of money people have to spend.

The federal government – which can run deficits – can provide assistance to states and localities to avert these “pro-cyclical” actions.

States Have Restrained Spending and Accumulated Rainy Day Funds

Many states have never fully recovered from the fiscal crisis in the early part of the decade. This fact heightens the potential impact on public services of the deficits states are now projecting.

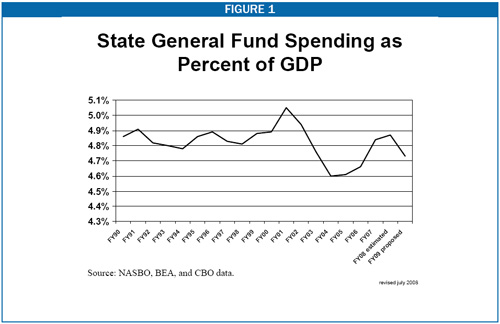

State expenditures fell sharply relative to the economy during the 2001 recession, and for all states combined they remain below the FY2001 level. (See Figure 1.) In 18 states, general fund spending for FY2008 – six years into the economic recovery – remained below pre-recession levels as a share of the gross domestic product.

In a number of states the reductions made during the downturn in education, higher education, health coverage, and child care remain in effect. These important public services were suffering even as states turned to budget cuts to close the new budget gaps. Projected spending as a share of the economy declined in FY2008 and is projected to decline further in FY2009.

One way states can avoid making deep reductions in services during a recession is to build up rainy day funds and other reserves. At the end of FY2006, state reserves – general fund balances and rainy day funds – totaled 11.5 percent of annual state spending. These reserves were estimated to decline to 7.5 percent of annual spending by the end of fiscal year 2009. Reserves can be particularly important to help states adjust in the early months of a fiscal crisis, but generally are not sufficient to avert the need for substantial budget cuts or tax increases.

Federal Assistance is Needed

Federal assistance can lessen the extent to which states take pro-cyclical actions that can further harm the economy. In the recession in the early part of this decade, the federal government provided $20 billion in fiscal relief in a package enacted in 2003. There were two types of assistance to states: 1) a temporary increase in the federal share of the Medicaid program; and 2) general grants to states, based on population. Each part was for $10 billion. The increased Medicaid match averted even deeper cuts in public health insurance than actually occurred, while the general grants helped prevent cuts in a wide variety of other critical services. The major problem with that assistance was that it was enacted many months after the beginning of the recession, so it was less effective than it could have been in preventing state actions that deepened the economic downturn. The federal government should consider aiding states earlier, rather than waiting until the downturn is nearly over.

|

APPENDIX |

||

|

State |

Source |

Notes |

| Alabama | Legislative Fiscal Office | |

| Arizona | Governor’s proposed budget | |

| Arkansas | Department of Finance and Administration | |

| California | Legislative Analyst Office analysis of Governor’s May revised budget | Assumes FY2008 gap carried over to FY2009. California has adopted measures to close $7 billion of this shortfall. |

| Connecticut | Office of Fiscal Analysis | |

| Delaware | Delaware Economic and Financial Advisory Council Revenue Forecast | |

| Florida | Florida Revenue Estimating Conference | |

| Georgia | Georgia Budget and Policy Institute | |

| Illinois | Calculated by Voices for Illinois Children based on the Governor’s proposed budget | |

| Iowa | Summary of FY 2009 Budget, Legislative Services Agency and Revenue Estimating Conference | This is the gap between projected revenues and spending before accounting for the expenditure limitation. |

| Kentucky | State Budget Director | Revenues falling short of projections. |

| Maine | Maine Revenue Forecasting Committee | FY2009 is the second year of the biennial budget. |

| Maryland | Maryland Budget and Tax Policy Center and Maryland Board of Revenue Estimates | Gap reflects $500 million in spending cuts assumed in special session bill plus the effect of lower revenue estimates. Adopted budget closed gap. |

| Massachusetts | Executive Office of Administration and Finance | |

| Michigan | May 2008 Consensus Revenue Forecast | |

| Minnesota | Minnesota Department of Finance | |

| Mississippi | Mississippi Economic Policy Center | |

| Missouri | Missouri Budget Project | |

| Nevada | Governor’s office | FY2009 is the second year of the biennial budget. Governor has taken actions to close gap, some of which are being contested. |

| New Hampshire | Press reports | |

| New Jersey | Governor’s proposed budget | |

| New York | Division of Budget | |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma State Board of Equalization | |

| Ohio | Ohio Office of Budget and Management | |

| Rhode Island | Office of the Senate Fiscal Advisor of the Rhode Island Senate | |

| South Carolina | Revenue Forecasting Council, budget hearing | |

| Tennessee | Governor’s office | |

| Texas | Center for Public Policy Priorities | |

| Vermont | Public Assets Institute | |

| Virginia | Commonwealth Institute | Executive actions plus adopted budget closed gap. |

| Washington | Washington State Budget & Policy Center | |

| Wisconsin | Legislative Fiscal Bureau | |

End Notes:

[1] California has partially addressed its shortfall.

[2] Analyses prepared by the legislature or by nonprofit fiscal organizations in these seven states found that expected revenues will fall short of the amount needed to support current services. The appendix to this paper shows the sources of these analyses.

[3] For more detailed information see Facing Deficits, Many States are Imposing Cuts that Hurt Vulnerable Residents http://www.cbpp.org/3-13-08sfp.htm.

By Elizabeth C. McNichol and Iris Lav

Updated August 5, 2008