Would you want other people to know, all day long, exactly where you are, right down to the street corner or restaurant?

Unsettling as that may sound to some, wireless carriers are betting that many of their customers do, and they’re rolling out services to make it possible.

Sprint Nextel Corp. has signed up hundreds of thousands of customers for a feature that shows them where their friends are with colored marks on a map viewable on their cellphone screens. Now, Verizon Wireless is gearing up to offer such a service in the next several weeks to its 65 million customers, people familiar with it say.

WSJ’s Jessica Vascellaro tests out Loopt’s new buddy-tracking device to see whether it’s helpful for hooking up with friends or just another invasion of privacy.

Making this people-tracking possible is that cellphones today come embedded with Global Positioning System technology. With it, carriers have already offered mapping features such as turn-by-turn driving instructions. But they long hesitated to offer another breakthrough made possible by GPS — tracking of cellphone users’ whereabouts in real time — because of privacy and liability concerns.

Now, increasingly, the wireless industry is deciding that location tracking has so much sales potential that it’s worth the risks, so long as tight safeguards are in place. It’s a result of the convergence of GPS with another digital phenomenon: a generation of young people who are comfortable sharing a great deal of personal information on social-networking Web sites and eager for still more ways to stay connected. The initial target market of location-tracking services: 18- to 24-year-olds.

Vivek Agrawal, a 22-year-old composer in Palo Alto, Calif., uses the service offered by Sprint to know where 10 friends are at any given time and organize impromptu get-togethers. “I’m using it amongst my closest friends,” he says. “Those are the people that I’m used to asking questions like, ‘Where are you?'”

The wireless industry is cracking open this new market gingerly, mindful that it could face a huge backlash from consumers and regulators if location-tracking were abused by stalkers, sexual predators, advertisers or prosecutors. “When it gets to privacy, that’s quite frankly an area where we can’t afford to make any mistakes,” says Ryan Hughes, a vice president at Verizon Wireless.

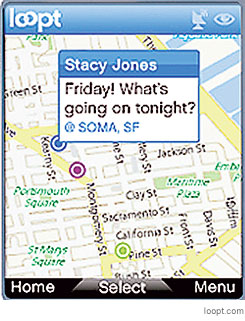

Like Sprint Nextel, Verizon Wireless will use a service called Loopt, led by a 22-year-old, Sam Altman, who created the software as an undergraduate at Stanford. Mr. Altman says he is well aware of the dangers of misuse. “It’s one of those things, the more you think about it, the more ways you can figure out a creep could abuse it,” says Mr. Altman, who, as chief executive of closely held Loopt Inc., in Mountain View, Calif., still carries a messenger bag to meetings. “I think people realize that unlike a telemarketer call, which can be annoying, a location-based service could be an actual physical safety risk.”

He set out to give Loopt strict rules to prevent misuse. The most significant is that cellphone users who sign up can make their whereabouts available only to a network of friends who also buy the service. They can view each others’ location any time, with the proviso that users always can temporarily turn off location-tracking. The service doesn’t continuously update, because that would overtax the carrier networks and consume too much battery life; it “refreshes” every 15 minutes or so, and users can always manually refresh.

Mr. Altman added a couple of other rules to make the service safer. Children under 14 can’t sign up. And for the first two weeks, new users are to get several messages reminding them that the service is on and that they’re being tracked.

Still, he encountered some roadblocks at Sprint. In the fall of 2006, Sprint was considering letting a subsidiary, Boost Mobile, offer Loopt to its customers. Sprint General Counsel Len Kennedy called Mr. Altman to a meeting and grilled him for two hours about the risks of users broadcasting their location to the world.

To ease Sprint’s concerns, Mr. Altman agreed to a change that more rigorously limited the service to a network of friends. He changed the software so users couldn’t troll outside their friend network for other cellphone users whose location might possibly be visible. “We wanted to make sure profiles weren’t viewable just wide open on the Net,” says a Sprint attorney, Frank Triveri.

In November 2006, Sprint let its subsidiary offer Loopt to Boost customers, who buy cell service through a prepaid package rather than an annual contract. And last July, Sprint offered Loopt to the far more numerous customers of its main cellular service. In addition, Sprint has a similar-working “child locator” service aimed at parents, which it recently made available on all Internet-enabled Sprint cellular handsets.

A disclaimer that must be signed by Sprint customers who take the service suggests how concerned Sprint is about liability. “Sprint is not responsible for the Loopt Service,” it says, and customers disclose their location “at your own risk.” The service is currently being offered free as a promotion, but Sprint will eventually charge a few dollars per month, as its Boost subsidiary does.

Loopt has a laborious registration process that involves scrolling through several pages of disclaimers and privacy notices. Once signed up, users get regular messages reminding them that location-tracking is on, a possible source of annoyance to subscribers.

Relaxed View

Some in the industry think wireless carriers are being too skittish. Richard Wong, a partner at venture-capital firm Accel Partners, says “operators are sometimes too careful around this issue and are stifling innovation to some degree.” He says the industry isn’t taking into account that younger consumers have a much more relaxed view about what constitutes an invasion of privacy than their parents.

Our City Forest, a San Jose, Calif., nonprofit that promotes tree-planting in urban areas, gives its employees phones equipped with the service, to help them coordinate while in the field. Employee Meghan Johnston, 18, gives the service a rave review, but says she wishes it also enabled her to post pictures of trees so experts could help her identify them. “It’d be nice to make it accessible to people outside of Loopt, but not creepily,” she adds.

New location-sensitive services are emerging at a rapid pace. Wireless carriers have long been able to get a decent lock on a user’s location by gathering data from cellphone towers. But the increasing pervasiveness of GPS-enabled cellphones has made it much easier for carriers to track users’ whereabouts. GPS is a network of earth satellites, developed by the Defense Department, that can determine an object’s location based on how long it takes for a signal to reach the object from satellites.

A service called Whrrl, from a Seattle company called Pelago Inc., will soon begin logging the places cellphone users visit — right down to the name of a specific establishment. For instance, if a user visits a Chinese restaurant, the system will automatically pinpoint the location, look up the name of the restaurant based on the address and allow the user to share that information with others whom the user selects. The service, which the company says has tens of thousands of users, will also recommend nearby places popular with a user’s friends by highlighting locations on a map.

An early version of Whrrl that can be downloaded through the phone’s Web browser requires users to enter their location manually. Pelago says it will launch the complete GPS-enabled version with a U.S. wireless carrier later this year.

Yahoo Inc. is jumping into the fray, too. Earlier this year, it announced a product for mobile phones called oneConnect that will integrate location-tracking into other communications services such as instant messaging. Yahoo says it will be available in the second quarter.

Verizon Wireless — a joint venture of Verizon Communications Inc. and Vodafone Group PLC — expects to roll out its service using Loopt in April. It is taking a cautious approach, drawing lessons from Internet companies that have taken heat over their more-freewheeling approaches to social networking. Watching Internet companies “has given us a sense of the laundry list of things that could go wrong,” says Mr. Hughes, Verizon Wireless’s vice president of digital media programming.

The largest U.S. wireless carrier, AT&T Inc., says it’s still weighing its options on location-tracking services, but notes that privacy is a top concern.

With Sprint and, soon, Verizon Wireless coming on board, location tracking is a rare cellular feature in which the U.S. industry is ahead of Europe’s and Japan’s. The reason is that U.S. regulators mandated several years ago that phone companies include location-tracking technology in handsets so public-safety personnel could track people’s whereabouts in emergencies.

But location-based services are also growing overseas. European mobile carriers are starting to offer subscribers turn-by-turn driving directions and computerized maps. Amsterdam-based GeoSolutions BV offers a service called GyPSii, which allows cellphone users to view the location of others who use the service, as well as pictures and videos they have uploaded. So far, users are downloading the application from the Web. But the company has announced plans to offer it through wireless carrier China Unicom Ltd. in time for this summer’s Olympic Games in Beijing.

Japanese wireless carrier NTT DoCoMo Inc. offers a service that allows parents to view the location of their children when they’re carrying certain GPS-equipped “Kids’ Phones.”

So far, the services and the privacy issues they raise are barely on the radar screen of regulators and others in the federal government. The Federal Trade Commission, however, has met with several location-tracking companies to prepare for a May workshop that will focus on advanced mobile services. “When you’re dealing with matters as intimate as someone’s location, I think you have to make sure that consumers have clearly and unambiguously agreed to be made part of the service,” notes one commissioner, Jon Leibowitz.

The Federal Communications Commission back in 2002 considered issuing regulations for commercial location services, but decided it was too early to delve into the issue. The agency says it hasn’t any plan to restart those proceedings.

The only relevant statute appears to be a 1999 law that says cell-service carriers must get “express prior authorization of the customer” to use or provide access to location information for commercial purposes. The sponsor of that law, Rep. Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts, says it may be time for an update. “As each new technology revolution takes place, you need a discussion about what the implications are for privacy,” he says.

Policing Itself

The wireless industry is trying to stay ahead of the debate by policing itself — and lobbying. Carriers are drafting a set of privacy standards for location services through their main trade group, CTIA-The Wireless Association. The rules, expected to be adopted in April, are being circulated with key officials on Capitol Hill and the FCC.

As the leading startup in the nascent industry, Loopt has mounted its own Washington outreach. Mr. Altman hired a tech-industry lawyer, Brian Knapp, as chief privacy officer. The two have made frequent trips to Washington to court officials in Congress, the White House, the FCC and nonprofit groups, explaining Loopt’s privacy policies and getting input on how to tweak them. The goal, says Mr. Altman: to “keep from getting legislated out of business.”

After Mr. Knapp visited the National Network to End Domestic Violence last June, Loopt agreed to make its privacy controls easier to find on cellphones. It added a feature that enabled users to give a false location to throw off a stalker.

Another issue that’s beginning to get attention is under what circumstances carriers or service providers like Loopt should have to turn over real-time location information in criminal investigations. Federal magistrates have been split on what authority a prosecutor needs to tap location-tracking services: a simple subpoena, as would be required for an individual’s call records, or an order based on “probable cause,” a much higher standard used for legal wiretaps.

Mr. Markey says lawmakers and regulators should be giving the privacy issues surrounding location services serious thought, rather than waiting for a high-profile incident of corporate or government misconduct that brings the issue into sharp focus.

“There has to be a national debate about what the privacy implications are,” he says.

Write to Amol Sharma at [email protected] and Jessica E. Vascellaro at [email protected]

By AMOL SHARMA and JESSICA E. VASCELLARO

March 28, 2008

Source: The Wall Street Journal